In this weekly column, one writer will send another a new piece of writing about a film they have been watching and pondering over, in the hopes that this will prompt a connection—emotional, thematic, historical, or analytical—to a different film the other has been watching or is inspired to rewatch. This ongoing column will be in the spirit of many past Reverse Shot symposiums, in which writers found connections between seemingly disparate cinematic works, and it will also help us maintain personal connection among our writers and our readers at this uncertain moment.

Manhunter

I have this idea that every era’s ultimate artistic subject is its discovery of the obstacles standing in the way of intimacy. I’m attracted to this idea in part because it’s sufficiently half-baked and reductive to encompass everything, from The Age of Innocence, with its Gilded Age moralism, to Frank Tashlin’s Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, at the conclusion of which Jayne Mansfield plaintively asks her long-lost love, Groucho Marx, why he never tried to kiss her, and he replies, “I never could get close enough” (a joke at the expense of her space-age bosoms, which Mansfield surely appreciated better than anyone). Seen this way, expressions of romance, violence, anarchy, satire, etc., are attempts to test, flaunt, and remake the structures that prevent us from being true to each other.

From the vantage of spring 2020, it’s not hard to hypothesize what contemporary conditions would keep Jayne and Groucho, or Newland Archer and Countess Olenska, from coming kissingly close; the challenge for art is to explore how that would actually feel for them. Right now, here in Brooklyn, I have everything I need, while being cut off from the flow of existence; all I can really do is try to divert a stream of torrential reality my way, through Zoom keyholes and onrushing social-media scrolls. I want to be easy and articulate, but I feel brutish and unwieldy, like I’m trying to maneuver a video-arcade claw machine to pick up individual grains of sand, which is to say I feel like a character in a film by the cinema laureate of blocked intimacy and hyperreal modernity, Michael Mann.

Mann’s great subject is men reaching out—men hunting. Manhunter could just as easily be the title of Heat or Public Enemies, and even The Last of the Mohicans, with its overwhelmingly potent depictions of heterosexual lust, has as its twin poles the doubled figures of Hawkeye and Magua, two orphans who circle each other urgently, ardently, as if to reintegrate a split self. In Manhunter, from Thomas Harris’s novel, FBI profiler Will Graham (William Petersen) is lured out of retirement to track the familiacidal-maniac home invader known as “the Tooth Fairy” (Tom Noonan). As with his previous pursuit of Dr. Hannibal Lecktor (Brian Cox, originating the role though not the spelling), Graham gets In Too Deep, walking in the Tooth Fairy’s footsteps and describing the killer first as “him,” then as “you,” and finally, inexorably, as “I.” Graham peers into the same glass houses as the killer, pores over the same home videos, until he sees the Other reflected back at him—the same intimacy the Tooth Fairy seeks in the eyes of his victims.

One of the many things I have come to love about Mann over the years is the dopey, humorless intensity of his music tastes, which sound to me like a struggle towards intimacy. Needle-drops like Manhunter’s screamy, resolutely mid-tempo end-credits song “Heartbeat” are clenched rockist libido at the outer limits of its emotive range, affected and affecting in the same way as the lockjawed, yearning men who populate his films. In turbulent, violent worlds, Mann’s characters fixate on still points of wisdom: across three decades, in Manhunter, in Heat, in Miami Vice, they repeat that “time is luck,” a basically meaningless mantra but one with which I have, of late, struggled to find much fault. They cling to these truths with the same meaty, desperate grip with which they cling to each other. Think of Chris Hemsworth palming Tang Wei’s entire head in Blackhat, holding her in his enormous hand like a tiger carrying its cub in its jaws; of Colin Farrell, in Miami Vice, reaching across to Gong Li’s seatbelt before he makes his go-fast boat go even faster; of Al Pacino commandeering an LAPD chopper so he can ask Robert De Niro out for coffee; of Petersen in Manhunter softening his voice to a fearful whisper as Graham tries to explain what he does to a son he knows is terrified of his father.

Watching Manhunter returned me to a state as animalistic as childhood, hearing the sound of adult voices in the next room. The backstory is elaborate and the exposition oblique: it seems we’ve started somewhere in the middle, and have to catch up, and baroque motifs, like the Tooth Fairy’s love of William Blake’s “The Tyger,” arise from nowhere. The dialogue is murmured, or echoing. The lighting scheme color-codes aggressively: cold nocturnal blues for the murder houses, like the light from a TV hitting the walls after everyone has gone to bed; in FBI headquarters and Lecktor’s cell, a white so bright it hurts your eyes; lurid shades of red and green in the Tooth Fairy’s lair. It’s a quarantine aesthetic: every room is its own headspace, its own world, in a way that also predicts the digital collage of Collateral or Miami Vice, which rarely orient their viewers in conventional coverage or repeated setups, so that it’s hard to hold on to any objective sense of scale. It gives you a woozy, restless, disassociated feeling that’s borderline incoherent but turned all the way up; watching a Mann film feels like pacing in a glassy cage, searching for some kind of anchor point in the distance, somewhere beyond this experience that’s equal parts high-tech and feral. —Mark Asch

Sambizanga

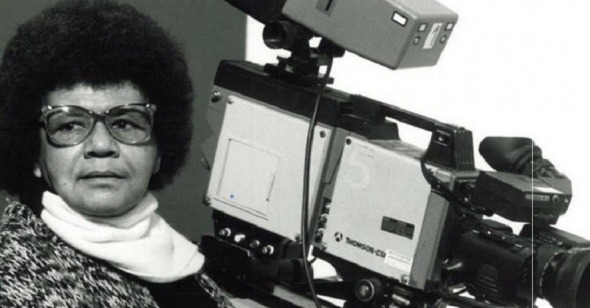

Echoing your sentiment on using social media and “Zoom keyholes” to cope, I have been maneuvering my way through Google drives with downloadable films in them, shared log-ins across streaming networks, and participated in video chat link-ups to discuss what we’ve just watched. In the absence of communal watching in physical spaces, one of the most moving experiences for me was taking part in the The Legacies of Sarah Maldoror (1929-2020) organized by Daniella Shreir and Yasmina Price via Another Gaze: A Feminist Film Journal.

This discussion group invited us to spend time with the films of Sarah Maldoror, a Guadeloupean filmmaker, political activist, and pioneer who set forth to make vital work within the pantheon of Pan-African cinema. Her films highlight themes about the struggle for liberation, shed a light on important Black cultural figures, and foreground the experiences of African women. She once said, “African women must be everywhere. They must be in the images, behind the camera, in the editing room and involved in every stage of the making of a film. They must be the ones to talk about their problems.”

Another Gaze’s program provided us with a perspective on the breadth of the filmography, theater work, and life of this director, who passed away last month. After spending a week or two with the films available to us, we then became active participants in a Zoom discussion. Aspects of the conversation often spilled onto Twitter, with each of us commenting in real time on the themes in Maldoror’s work, specifically films like Sambizanga (1972).

In the film, set in Angola, Domingos, a revolutionary looking to overthrow Portugal’s colonial rule, is taken from his home by armed forces. From there we follow his wife, Maria, on her journey to get answers about where Domingos is located, newborn baby in tow. This journey doesn’t just require following the trail of information by foot but also seeing how that information travels in spaces like prisons via word of mouth, an important mode of communication. My synopsis feels as though it fails to encapsulate the brilliance of Maldoror’s film, which was at one point banned in Angola prior to the toppling of colonial power in 1974.

After watching Sambizanga and the rest of the film program (which consisted of her short films Monangambée [1968], Et les chiens se taisaient d’Aimé Césaire [1978], and Léon G. Damas [1994]), we all convened on Zoom to parse through the themes of her work. The “we” consists of the brilliant Black women who read excerpts of Fanon and Césaire, and then the panel that took place afterward with filmmakers, curators, and scholars in the lineage of Maldoror discussing how they first came to her work. Also her daughters Annouchka de Andrade and Henda Ducados shared anecdotes of their mother’s life with us, giving us a peek into the process of preserving her legacy, be it through the restorations of her films or discussing what inspired her in conversation, where those stories will live on amongst us.

Key ideas that resonated with me included the ways in which love and motherhood are part and parcel of revolution, the importance of poetry as a gateway to a better understanding of image-making, the necessity of pulling from other mediums to better inform your craft, and that political storytelling isn’t in opposition to beauty and aesthetics. All of these ideas, which would break off into deeper conversations pulling from post-colonial Marxist theory and poetry, served as an oft-needed reminder that nothing is new and we all have creative ancestors laying the foundations for our own work.

When I first saw Sambizanga last summer, I was in the midst of wanting to explore new narratives, which is also part of the driving force behind what I’ve been doing in quarantine: familiarizing myself with work that I hadn’t been privy to. The driving principle that led me to Film Forum was a leap into this then-unfamiliar world. I tagged along with a friend who was helping me visualize what would be my own first film. We’d been watching new things and then using them to inform what we’d end up shooting later that summer. Maldoror’s scenes of community subconsciously validated the thesis of what I want my own oeuvre to be.

One of my favorite moments in Léon G. Damas is when Maldoror is on the streets of French Guiana asking Black students who their favorite poets were and which ones they’re learning about in school. At the same time she’s also maintaining a narrative about Damas, poet and founder of the Negritude movement, who is described by Césaire as a “Negro of the diaspora; an uprooted Negro”—a description that I found profound in that he was an intra-communal figure both connected to and speaking to me as a Black woman regardless of my place in the world. Yet, regrettably, much like those same students, this was my first time hearing of him. I, too, was receiving an on-the-ground education by way of Sarah’s filmmaking.

The act of disseminating information among each other for the greater good of the collective is a major theme in much of Maldoror’s work. Her films, as the panelists discussed, operated in a space of plurality not fixated or concerned with one specific narrative but seeking to connect to and explore histories—of people, of places—and calling upon us to use that knowledge to “remake the world differently,” a refrain heard throughout the conversation. These are all strategies that must be employed in our contemporary moment.

To take part in the discussion around her legacy with other thinkers and creators allowed for a sense of communion that I’d been longing for without even realizing it. It got my dormant brain cells working and solidified the importance of collective action and seeing each other through. It fed me spiritually, and gave me new readings to seek out and set me on a path of better understanding. The closing remarks emphasized the need to look towards a future—precisely my tactic to get through the other side of all of this. —Tayler Montague